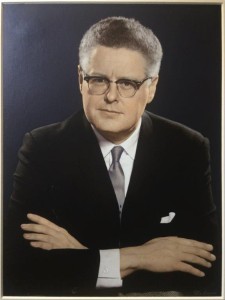

November 2015 is the 100th anniversary of architect John O’Malley’s birth, making now an opportune time to share more information about his expansive body of work. Relatively unknown today, during his lifetime O’Malley was incredibly prolific, designing more than 150 structures, almost exclusively in the New York region. He had a long affiliation with both of New York City’s Catholic dioceses, the New York Diocese (Bronx, Manhattan, and Staten Island) and Brooklyn (Brooklyn and Queens), as well as the Diocese of Rockville Centre (Nassau and Suffolk Counties), which became its own division in 1957.

O’Malley studied architecture at Pratt Institute and engineering at Columbia University and briefly worked in the office of Joseph Mathieu, a church architect primarily working in the 1930s, 40s, and early 50s. In 1950 O’Malley opened his own practice and by 1954 work had quickly taken off. One of his first church commissions was a renovation project at St. Francis de Sales in Manhattan; among other things O’Malley constructed a new entrance staircase in an extremely constricted amount of space. By the early 1960s, he was designing several churches, school buildings, rectories, and other associated structures a year.

In 1962, the Queens Chamber of Commerce took note of his talent and commended three of his projects in their annual Chamber of Commerce Building Awards program. The most significant of these projects was St. Michael’s in Flushing, a large new church which replaced an older structure nearby. The others were a modest auditorium for St. Gertrude’s in the Rockaways and St. Elizabeth’s School, a relatively traditional design in Woodhaven with a striking entrance mural. O’Malley went on to receive a total of nine awards from the Chamber of Commerce over the next nine years for Catholic-affiliated architecture.

O’Malley’s dedication to a project was absolute, he assisted a parish in all aspects of planning, from fundraising for the capital project to choosing the liturgical furnishings. His firm not only did major buildings but also did building assessments and minor renovations, and he became a favorite of the Dioceses, especially in Brooklyn and Queens. O’Malley helped guide many parishes through the whole process, including those with fewer resources such as St. Leo’s in Corona and St. Margaret Mary in Long Island City. In a letter from the pastor of St. Michael’s to the Bishop of Brooklyn, he notes that in addition to designing the new church, O’Malley sketched plans for a new parish convent as a personal favor to the pastor and at no cost to the Diocese.

St. Robert Bellarmine, 1969

By the mid-1960s, he was arguably the dominant church architect in Brooklyn, Queens, and Long Island, surpassing some of his older contemporaries like William Boegel and Beatty & Berlenbach who had longtime relationships with the diocese earlier in the century. In the case of one church, Beatty & Berlenbach were actually mentioned as architects for an earlier iteration of the project, which later when to O’Malley.

Also, unlike these more traditional firms, O’Malley’s designs evolved beyond the red brick and limestone that had long been favored. His designs are light, clean, and undeniably contemporary using brick in tans and oranges, striking stone and brick details on the exterior, and bright accessible interiors with colorful stained glass. His commissions contain original work by noted craftsmen like glass artist Albinus Elskus and mosaic artist Lumen Winter.

In the late 60s, he designed at least three round churches, Queens Chamber award winner, American Martyrs Church in Bayside and St. Mary Mother of Jesus in Brooklyn, a rarity for the time. This was just one example that demonstrates O’Malley’s interest in how the reforms of the Second Vatican Council were being interpreted in the construction of religious facilities. In these round structures the congregation sits in a semi-circle around the priest rather than the traditional layout with the priest at the head of the church. In addition, some of O’Malley’s churches lack communion railings, baldachins, and some of the other traditional elements that were slowly being abandoned.

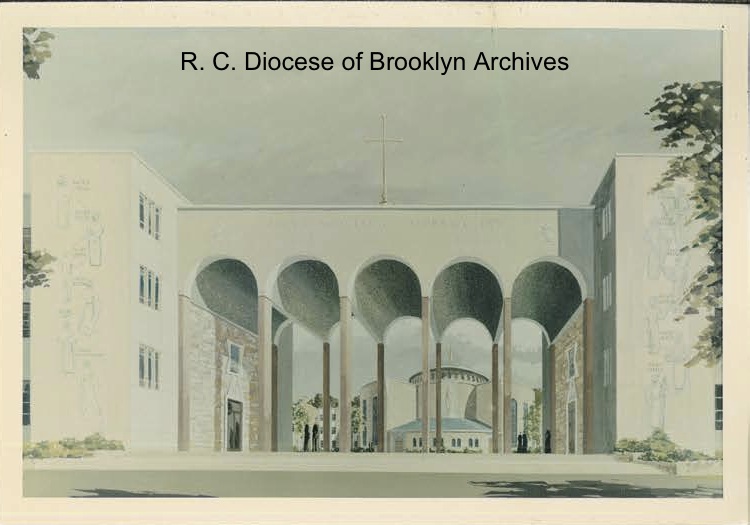

His most significant commission, constructed from 1963-1967, was Cathedral College of the Immaculate Conception, a completely new seminary for 400 students in Douglaston, Queens. The 27-acre campus, which still exists in part today, included residences for students and faculty, a central round chapel, auditorium, and athletic facilities all fronted by a monumental entrance portico.

Although the late 1960s were arguably the height of O’Malley’s output, work for the Diocese started to dry up as 1970 approached. He branched out, serving on a mayoral committee for architecture and designing other buildings including his own family residence in Plandome on Long Island. Sadly, shortly after moving his family into their new home he suffered a fatal heart attack in 1970 at the age of 54. Having been the lifeblood of his firm, it quickly shut down without him and the files were lost.

Today, people are beginning to reevaluate his work, looking at his modernist designs that in some ways were ahead of their time. Among those pushing to have John O’Malley known to a larger audience are his children; all 14 of them survive and today are working on several initiatives to promote their father’s legacy. We look forward to sharing more information with you in the future.

Special thanks to the O’Malley family for image of John O’Malley, project information, and support.

Sources:

“John J. O’Malley” Wikipedia.com.

Phone interview with Colm O’Malley and Therese O’Malley, 21 October 2014.

Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn, Diocesan Archives.